Every year I end up in this position come April and May. Nothing to eat. Er, except for a huge stash of frozen green beans, and they’re beginning to pall a little.

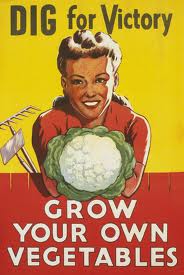

It may seem surprising to anyone who doesn’t grow vegetables – though obviously we all should (!) and this is an accurate depiction of me, by the way – but this is the time of year when home-grown produce is thin on the ground. Traditionally, it’s the season when labourers and peasants’ resources were at their most stretched and starvation was a real possibility.

It may seem surprising to anyone who doesn’t grow vegetables – though obviously we all should (!) and this is an accurate depiction of me, by the way – but this is the time of year when home-grown produce is thin on the ground. Traditionally, it’s the season when labourers and peasants’ resources were at their most stretched and starvation was a real possibility.

Happily that’s not (quite) the case now, but it can still be an issue for anyone who likes to grow as much of their own veg as possible. There just isn’t that much available. Brassicas and the like are mostly over by now, going to seed as the temperature increases, and nothing else has yet come on stream.

Admittedly there is a variety of kale which fills the gap – introduced to Britain in 1941, when it was most desperately needed – but I’ve lived on kale at this time of year before now and I’m not keep to repeat the experience. And that’s what it does: repeat. I shall say no more, but my decision has been a popular one. If you’d like to test it for yourself, Chiltern Seeds usually have Hungry Gap Kale. It’s frost resistant (not a problem for me), and it does have a good flavour, but… oh, yes; I said I would say no more. Instead I’m just going to stand in the garden and sigh.

We are still lucky though. Not only can we garden without the risk of enemy parachutists landing in the potato plot, we can supplement our stock with food from the shops. And even if we try not to fall back on that to any great extent, we do not have to actually can anything, though apparently one in five US households still do. Listen to Betty MacDonald on the perils of home canning in the late 1920s:

First you plant too much of everything in the garden; then you waste hours and hours in the boiling sun cultivating; then you buy a pressure cooker and can too much of everything so it won’t be wasted. Frankly I don’t like home-canned anything, and I spent all of my spare time reading up on botulism…

That risk still exists today: between 1996 and 2008 there were 48 outbreaks of botulism in the US that were directly linked to home-canned food, and botulism kills – nastily. To me, this doesn’t sound like something I should be doing; I’m thinking the Russian roulette scene in The Deerhunter, but with a jar of home-canned cauliflower.

Thank goodness we have freezers now (admittedly freezers full of french beans). Incidentally, the same over-production addiction – Betty MacD. noted that her neighbours were eating the season before the season before’s produce, and were still planting and planning on canning the current season’s stuff – applies today. I know I don’t need quite so many climbing beans this year, but guess what’s in the cold frame, ready to go out?

Thank goodness we have freezers now (admittedly freezers full of french beans). Incidentally, the same over-production addiction – Betty MacD. noted that her neighbours were eating the season before the season before’s produce, and were still planting and planning on canning the current season’s stuff – applies today. I know I don’t need quite so many climbing beans this year, but guess what’s in the cold frame, ready to go out?

And in a few months time they’ll have been blanched and be drying off, ready for packing and putting in the freezer…

I’ve seen all sorts of alternative suggestions for things to fill the hungry gap but I’m not sure I could live on asparagus – and though I wouldn’t mind trying the season is short and doesn’t actually fill the gap. However, these ‘options’ mostly come down to other brassicas – purple sprouting broccoli, spring greens, and more kales – and in my experience most of these are already bolting. Squashes, if seasoned well in a good autumn (and that’s a big ‘if’ for me here in Snowdonia) will keep, but even they are failing now, going a little squishy at the base or stalk or, alternatively, getting so hard you have to take an axe to them. Leeks can stay in the ground so they’ve been recommended, but by late April they’re generally sending up spectacular seed heads or are so woody as to be unusable. It’s that HG kale or diddly squat. Diddly squat, then.

Despite this, I rather like the hungry gap in a perverse way, even if I am fed up to the back teeth of frozen beans. It connects me one of the main reasons I bought a house with a decent garden: feeding myself. It reminds me that food should never be taken for granted, and that seasonality should be a factor in my diet. The more I rely on out of season foodstuff from a supermarket, the greater the negative impact on the environment. I know it’s only a small thing, but lots of small things make a bigger thing. And in my case, a giant vegetable soup. Or Spanish green beans. Or green beans with tomato. Or a green Thai curry featuring – you guessed – green beans. Or just plain green beans with tomato sauce and fish fingers (getting desperate here). Green bean terrine?

Hang on a second – there is something other than frozen beans, though I’m not quite sure it’s a substitute for tomatoes, spuds, onions, beetroot, courgettes. The rhubarb looks promising…

And, even if we haven’t all quite got back to the point where there are piglets playing about while we hang out the washing, the tradition of small-scale pig-rearing is also beginning to reappear.

And, even if we haven’t all quite got back to the point where there are piglets playing about while we hang out the washing, the tradition of small-scale pig-rearing is also beginning to reappear.

In semi-defence of the entire restaurant industry I must say that bad behaviour from customers often engenders the bad behaviour from staff, and there was some wry amusement last year at a cafe in Nice, which charged different prices for coffee according to how polite you were (photo courtesy Nice Matin).

In semi-defence of the entire restaurant industry I must say that bad behaviour from customers often engenders the bad behaviour from staff, and there was some wry amusement last year at a cafe in Nice, which charged different prices for coffee according to how polite you were (photo courtesy Nice Matin).

The plants are easy to identify (even easier once they’re in flower), they’re easy to gather and they’re prolifically present in hedgerows and woodland – and my garden – just about now. And now’s the perfect time, because the leaves are still young. Plus it’s the start of the hungry gap, the time when stored fruits and vegetables have been used up and the new season is yet to get going.

The plants are easy to identify (even easier once they’re in flower), they’re easy to gather and they’re prolifically present in hedgerows and woodland – and my garden – just about now. And now’s the perfect time, because the leaves are still young. Plus it’s the start of the hungry gap, the time when stored fruits and vegetables have been used up and the new season is yet to get going.